|

If you look up jargon under any style guide, you’ll either see the recommendation to avoid its use altogether or to use it with caution. Here you’ll find out why most writing authorities adamantly reject its use.

What is Jargon?

Jargon is technical vocabulary, or an informal idiom, that is field specific, meaning it is easily understood by people within that particular field. According to the Council of Science Editors Scientific Style and Format, jargon can be

“I TLC’d the reaction to find out when it was finished.” or “After workup, I NMR’d the crude mixture.” These terms may have sounded odd to researchers outside of our group, but we knew exactly what was meant by TLC’d and NMR’d. Here’s what it could have been if jargon wasn’t used. “I used thin-layer chromatography to find out when the reaction was finished.” and “After work up, I performed a nuclear magnetic resonance experiment on the crude mixture.” Notice how the spelled-out examples are more formal and longer: neither of which are necessary for conversation between peers. Why should you avoid jargon in formal writing?

In the above example, the student’s use of TLC and NMR as verbs wasn’t a problem in the informal discussion within a group meeting. As noted in the Chicago Manuel of Style, English nouns are commonly used as verbs and often appear as jargon first. Our research advisor was very strict in removing this jargon from research papers and presentations.

Why? Because jargon is precise to only some audiences, specifically audiences within your own field. Thus, jargon can limit the reach of your message! Jargon may exclude

“I thin-layer chromatographied the reaction to find out when it was finished.” “After workup, I nuclear magnetic resonanced the crude mixture.” Neither of these uses would make sense to someone outside the field, and they could cause confusion for a multilingual scientist who knows what NMR and TLC are but isn’t familiar with these terms being used as verbs. Furthermore, jargon can mean different things to different audiences. For example, the term turnover number “is defined as the maximum number of molecules of substrate that an enzyme can convert to product per catalytic site per unit time” in enzymology. But in organometallic chemistry, the turnover number is the number of moles of substrate that a mole of catalyst can convert to product. Notice that the number of catalytic sites and time are not accounted for in the organometallic chemistry definition. Here’s an example from Einsohn and Schwartz’s The Copyeditor’s Handbook: “Steep-learning curve” means learning easy information at a fast rate to some or learning difficult information (think walking up a hill) at a slow rate to others. Results of using jargon in formal communications

Ultimately, jargon can confuse and limit your audience. It makes your reader work harder to understand the message. In fact, the use of jargon in a paper title or abstract may reduce the number of the paper’s citations.

In a 2021 article, Martínez and Mammola found a significant negative relationship between the use of jargon in the title and abstract of 21,486 cave research articles and the number of citations the articles received. This finding likely applies to other fields. Also, Jargon was found to disrupt fluency and to disengage the audience in a 2020 study in the Journal of language and Social Psychology. Here, study participants reported lower scientific interest in the study and perceived understanding of the topic. Jargon: yea or nay?

Based on what I describe above, it is usually best to avoid jargon. Science and medical communication are already complex, and so it should be the writer’s goal to make the text as clear as possible, especially for a general audience.

But there are proponents of jargon use in STEM writing. Trevor Quirk, in “Writers should not fear jargon” an opinion piece for Nature, states that removing jargon eliminates important information. He gives the example of “photometry” and “spectroscopy”. Both are “methods of studying light”, but they are two distinct techniques. Thus, in highly technical papers intended for a specific audience, jargon may have a place, but you must use jargon with care. If you choose to use jargon, use it judiciously. Do you use jargon in your scientific writing? Drop a comment.

0 Comments

Why does my elbow still hurt?

I developed a repetitive strain injury in my elbow this past year. At first, I thought it was an injury from lifting; I decided to rest my arm and let it be. However, the pain got worse. I couldn’t grip things with my left hand; I couldn’t sleep without propping my arm on a pillow; I couldn’t put a jacket on without wincing. After 4 months of this pain, I finally decided to see my doctor. It took her less than 5 minutes to diagnosis the problem as tennis elbow, a type of repetitive strain injury. Since I don’t play tennis, I may never know what repetitive movement caused this injury (dishwashing, maybe?), but now I know how to recognize the signs and to reduce my risk.

Keep reading to find out more about repetitive strain injuries and how to reduce your risk of developing one from computer use. What is Repetitive Strain Injury

Tennis elbow is a common name for a repetitive strain injury (RSI) known as lateral epicondylitis. This is caused by overuse of the muscles and tendons located where bone and tendons join in the elbow. You may have heard of other RSIs, including golfer’s shoulder, carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve compression), and stylus finger. These are all repetitive strain injuries that affect different parts of the upper extremities. As Johansson describes in his informative book What You Can Do About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Other Repetitive Strain Injuries (Contemporary Diseases and Disorders), RSIs are also known as

The Cleveland Clinic gives a good overview of what RSIs are and how they develop. Briefly, they all stem from microinjuries in joints and ligaments that occur repeatedly during daily activities. The body doesn’t have time to heal these micro wounds because the injury keeps occurring (think typing). We are all at risk of RSIs because of the repetitive movements of jobs, sports, and other hobbies, including music! The association between repetitive movements and work has been extensively studied and reviewed. RSIs are very costly to employers in the form of lost work hours and costly to employees due to pain, prolonged injury, and lost income. As described in a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best way to combat the problem of work-related RSIs is to implement work practices and environments that reduce the risk of developing these injuries. These practices include

RSIs at the desk

Extended computer use is a well-known risk factor for developing an RSI. A recent literature review states that more than 50% of computer users experience some form of MSD, with the most common areas affected being the back, neck and shoulder. Unfortunately, if you’re a writer, editor, or administrator (and many others), your job probably involves extended computer use and sitting for long periods. So what can we do?

How to reduce the risk of RSIs in editing and writing

In a 2005 in-depth review on MSDs and computer work, Wahlström cites studies on the association between computer work-related injuries and muscular load, postures and movements, and force. To reduce work-related—including computer work—risk of RSIs, the field of ergonomics emerged. Ergonomics entails modifying a work environment to reduce the repetitive motions or postures that increase the risk of RSIs. As I stated above, this is a type of engineering control: modifications of the types and setup of chairs, desks, keyboards, and monitors can help reduce the risk. Dygma gives a great summary of how to ergonomically set up your work station in their How to Prevent RSI with an Ergonomic Setup article.

Here is another good article with 10 suggestions for preventing RSIs. Aside from an ergonomically setup workstation (discussed above), you should take breaks from your desk (at least every hour), use good posture and support your back and arms, and reduce the amount of keyboard use. Tools to reduce mouse and keyboard use

So how does an editor or writer reduce keyboard and mouse use. In my experience, my job is typing and mouse work! Each keystroke requires pressure from a finger. And if you add up all the keystrokes over 8 hours of computer work, that’s a lot of pressure. For an interesting and high-level discussion on the pressure of typing, check out this post on keyboard switch forces.

To reduce the number of keystrokes and mouse movements throughout the day, you can try the following:

Macros

Macros are little computer programs that automate repetitive tasks. Paul Beverley has an outstanding list of macros that are free to download and use. He also has YouTube videos about how to use macros in writing and editing.

Do you need to make a list of all the hyperlinks in a document? There’s a macro. Do you need to find the next highlighted item? There’s a macro. Do you need to remove all highlights and/or text colors? Yes! There’s a macro. Check out my previous post on Macros to find out how I use these wrist-saving tools! Shortcut keys

Another way to reduce the number of keystrokes (and mouse use) is to use shortcut keys. Google shortcut keys to find lists of the shortcuts that are already within your writing software. Here’s just a few of the ones I use regularly.

You can also set your own shortcut keys. And yes, you can assign shortcut keys to macros! (I highly recommend this for macros you use while editing: “InstantJumpUp”, “HighlightFindDown”, “GoogleFetch”, etc.) To customize shortcut keys, go to your ribbon and right click. Click on “Customize the ribbon…”. Click on “Keyboard shortcuts: Customize” from there you can assign any combination of keys to many different commands. Have fun! Text Expander

Text expanders are tools that allow you to automate repetitive typing. They use snippets, which are shortcut phrases that insert long phrases, sentences, and blocks of text. Check out this post for a comprehensive guide to text expanders.

When I’m editing, I often leave the comment “Please ensure that my change doesn’t alter your intended meaning.” That’s a 10-word sentence that I type in almost every comment bubble. If I used the snippet, pec, then the text expander would automatically insert the full sentence. This saves time and pressure on my fingers and wrists. Awareness is key!

RSI is a serious injury that we may all be at risk of developing. With a few changes in habits and useful tools, we can reduce our risk of this costly disease. Do you have tricks for reducing the risk of RSIs? I’d love to hear from you.

As a copy editor, one of the most common punctuation mistakes I encounter in STEM writing is the use of a hyphen when an en dash is needed. Do you know how to correctly use the en dash in scientific writing? Read on to learn how and when to use this misunderstood punctuation mark.

What is an en dash?

Can you pick out the en dash from the picture? Here’s a hint: longer than a hyphen, but shorter than the em dash. And not to be confused with the minus sign. Common knowledge says that the en dash is so named because it is the approximate width of “N”. However, the name origin is more complicated. As described by Matthew Butterick in hyphens and dashes, “em and en refer to units of typographic measurement, not to the letters M and N.”

According to the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), the authoritative style guide for writers and editors that I describe here, "Hyphens and the various dashes all have their specific appearance…and uses…. The hyphen, the en dash, and the em dash are the most commonly used. Though the differences can sometimes be subtle—especially in the case of an en dash versus a hyphen—correct use of the different types is a sign of editorial precision and care." In UK English style the en dash with space before and after replaces the em dash, but this use of the en dash won’t be discussed further because it is atypical in US English style. How to us the en dash in science writing?

Recently, when I wanted to reviewing the rules on en dash usage in science writing, I grabbed my copy of the “Best Punctuation Book, Period” by June Casagrande. I love this book. It is very readable and easily searchable. Casagrande has a section for each punctuation mark, which includes a Punctuation Panel’s, made up of professional copy editors in news media and book publishing, preferred usage of the mark. As expected, the chapter on the en dash is quite short. However, I did a double take when I read, “The en dash…applies solely to book style. It does not exist in news, science, or academic style.” WRONG!

The en dash has very specific uses in STEM writing. The en dash is used to

Use in compound adjectives

Both CMOS and the American Medical Association (AMA) Manual of Style 11th edition prescribe use of the en dash when the compound adjective has an open element or already-hyphenated element. This helps avoid ambiguity.

For example: From CMOS, Chuck Berry–style lyrics (here, the name “Chuck Berry” is a known open unit, but it is a compound adjective with “style”) From the AMA, non–English-language journals Indicates equal weight

When a compound adjective has two components that have equal weight, the en dash is used. The American Chemical Society (ACS) and the American Psychological Association both describe this usage, known as the peer en dash. This includes collaborators of scientific findings or joint authorships.

Here are examples.

Numerical ranges

Another use of the en dash is to indicate inclusive numerical ranges (no spaces before or after the en dash). Use it for dates, times, data, and so on.

“The graph shows the mean of the data from multiple biological replicates (n = 3–6).” However, don’t use the en dash when “from” precedes the range—the word “to” is used instead. “Participation in the study was measured from May 2010 to April 2012.” Furthermore, if one of the numbers is negative, then the en dash should not be used. “Over the last week, temperatures were −10 to 23 °F.” Not “−10–23 °F”. Follow your style guide of choice to determine if units need to be repeated within numerical ranges. Of note, the AMA style guide 11th edition uses hyphens for numerical ranges. WEIRD! Chemical Bonds

Perhaps my favorite use of the en dash is in the chemical bond as prescribed by ACS. This is near and dear to my heart as I spent 6+ years working in chemistry and chemical biology. Here the en dash indicates a single covalent sigma bond.

H3C–OH R2C–C(H)=O Notice that the equal sign (same width as the en dash) denotes a double covalent pi bond. Yes to the en dash!

The en dash has specific uses in science, and it’s important for clarity, formality, and professionalism to understand the different uses. Although CMOS recommends using other punctuation instead of the en dash or completely recasting the sentence, I suggest using the en dash without reservation. What do you think?

If you don’t know how to start writing your research paper, you are not alone. According to the Berkeley Student learning Center Before You Start Writing That Paper guide, “all writers face the dilemma of looking at a blank computer screen….” Staring at a blank page can be daunting even when all the data is analyzed and the outcomes of the research are known. Google search “writers’ block” or “start writing”, and you’ll find thousands and thousands of hits about cures and strategies to overcome this common challenge.

So, what is the answer to writers’ block in STEM writing? Storyboards! Here, I describe how to use graphics (figures, tables, schemes) to storyboard for your research paper. What are storyboards?

As defined by the Nashville Film Institute, storyboards are graphical representations of a story’s step-by-step progress. Storyboards have been in use since the 1930s in the film industry. As described, storyboards help

Storyboarding for STEM research is not new. Check out this YouTube video on three different text methods to storyboard for science writing from the University of Guelph’s Writing in the Sciences (WITS) project. According to WITS, science writing storyboards are specifically used to

Identify the scenes.

When I was in graduate school and about to write my first paper, my research advisor gave me this advice, “Make the graphics first.”

If you haven’t already done so, you need to compile and analyze the data from your research. Overall, graphics should be concise, meaningful, and easy for your audience to understand. Graphics include

Generating the graphics doesn’t have to be a formidable challenge, it may be straightforward or even fun. Because my project was a synthesis, my schemes depicted the path from starting materials to products, with intermediates along the way. But for other papers, I needed to analyze data and use charts and graphs to understand the information and present it well. Identify the message.

While you make the graphics, mentally describe them—or take notes. This step is like making an outline: the graphic is the heading and each heading should have multiple points of discussion. By the time you finish the graphics, you should be able to communicate the type of data presented by the figure, how the data was collected, how the data could be interpreted, and how it is relevant to the main research claim. This is the message (points) of the storyboard (outline).

Logical flow of scenes to tell the story.

After organizing the research outcomes into clear and concise graphics, the graphics must be arranged to ensure a logical flow of the information, that is, a compelling story. By arranging and rearranging the order of the graphics—before any text is written—you can determine how the graphics are related and how to transition from one graphic to the next. Take time with this step. You may discover that a graphic doesn’t contribute to the current story but should still be reported in the supplementary information. Most importantly, it should be clear if more evidence is needed to support your claim or if there is missing information that needs to be addressed.

Filling in the details and drafting the paper.

Now it’s time to fill in the details. Once the graphics are in a logical order, start writing about the graphic using the points you already compiled. What type of data was collected for the graphic and why? What does the graphic show? Does it support or reject the claim? Did the data in this graphic lead to more questions that substantiated collecting more data? And so on.

Because the order of the graphics has been extensively explored to enhance logic and flow, transitioning from one to the other should be easy. Finally, the story that has unfolded from your data-derived visuals will determine what is included in the introduction and concluding sections. Do you know someone who could benefit from this approach to research paper drafting? Share my blog on LinkedIn.

Whether you're a new writer struggling with sentence structure and grammar or an experienced writer who wants to ensure they get every point across clearly, a style guide is the answer.

But not every style guide is created equal. For most writers, there’s one that I recommend above all others--The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS). Read on to learn how it was developed, why it will strengthen your writing, and the benefits of an online subscription over a hard copy edition of the text. What is CMOS?

According to its website, The Chicago Manual of Style is “the venerable, time-tested guide to style, usage, and grammar. . . . It is the indispensable reference for writers, editors, proofreaders, indexers, copywriters, designers, and publishers, informing the editorial canon with sound, definitive advice.”

The University of Chicago Press introduced the style guide in 1891 as "The University Press style book and style sheet." Initially, it was used as a style sheet, or common set of rules, to correct inconsistencies and find typographical mistakes across the university press. The 12th edition (1969), complied by Catherine Seybold (1925–2008) and Bruce Young (1917–2004), was a revision that solidified the position of CMOS as the industry leader on style matters. It is now in its 17th edition, with over 1,000 pages in the print edition and over 2000 hyperlinked and cross-referenced paragraphs. It is the authoritative style guide for fiction and non-fiction books and popular magazine articles. Why is CMOS important to a science writer?

If it’s the authoritative style guides for books and magazines, why does it matter to a science writer? Different scientific fields or publishers, such as the American Chemical Society, the American Institute of Physics, and the American Medical Association, have different style guidelines. Yet many of these field-specific style guides are based on CMOS (check out the subscriber testimonial from the American Meteorological Society), even if they disagree about comma placement or hyphenation rules. You’ll find that the fundamentals of grammar and writing, such as sentence structure and sentence parts, remain the same across them all. Notably, there is even a scientific companion to CMOS, Scientific Style and Format, that was developed by the Council of Science Editors to be an indispensable guide to science writers.

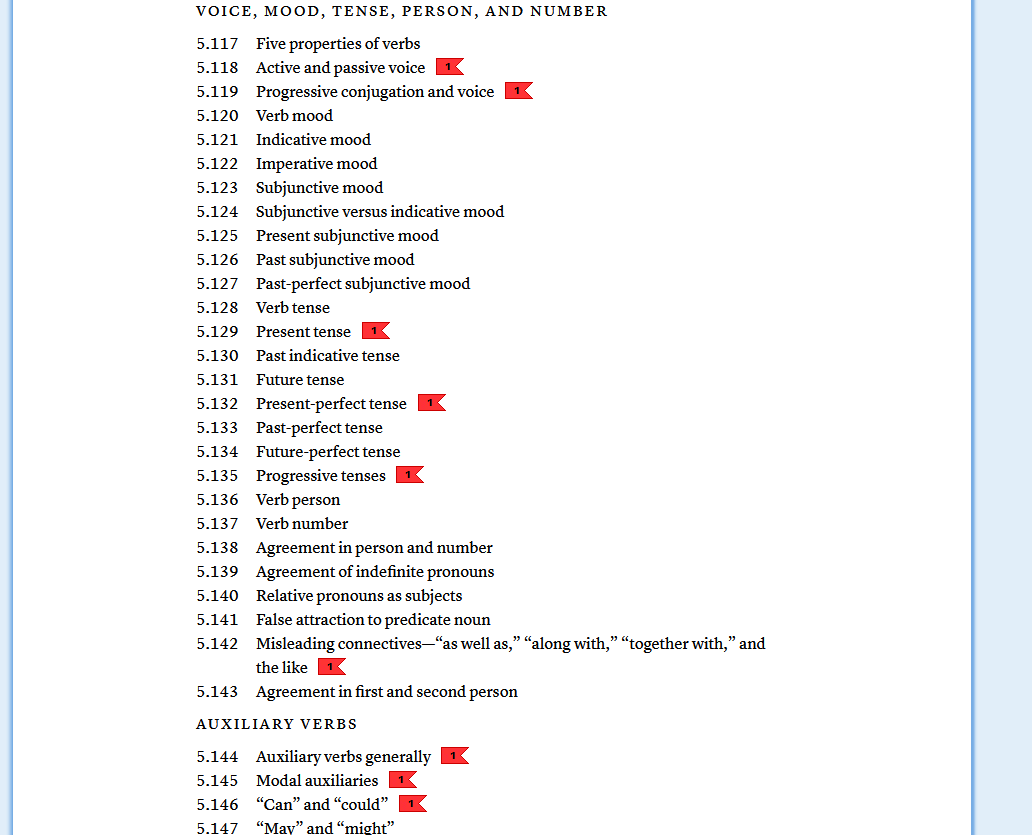

No matter your scientific discipline, you need to understand fundamental guidelines and conventions to share your message logically and persuasively. Within "Part II: Style and Usage," CMOS has extensive chapters explaining grammar fundamentals and the role of punctuation. This section is an invaluable resource when learning to write effectively in any scientific field. How do I use CMOS Online?

Because the hard copy of CMOS is over 1,000 pages (yikes!), I recommend getting an online subscription. Although some prefer to read the hard copy, which feels good in the hand, with an online subscription, you can

Keyword search the entire contents of CMOS

Submit a question to the Chicago Style Q&A

If you can’t find an answer to a style question, CMOS Online has a robust Q&A section. You can submit a question, browse questions, and get alerts. Members of the manuscript editing department answer questions regarding CMOS conventions not found in the style guide or a dictionary.

You can check out the answer to this question from the Latest Q&A page: Can you please add “wise” to the hyphenation table? I’m curious if you would use a hyphen in a sentence like “Accessibility-wise, my favorite city was Tokyo.” Access the online Users' Forum

Although, questions and answers are accessible by anyone, the user’s forum is specifically for subscribers. The forum is organized by category (i.e., copy-editing, business), then topic (punctuation, tables and illustrations), then threads and posts. Here you can reach out to others who may have the same problem you’re struggling with.

Access common-problem guides

Two important guides, the “Hyphenation” and the “Good usage versus common usage” guides, are readily available. These are invaluable to writers, even writers of scientific journal articles! Sometimes, you'll wonder, "Do I hyphenate this word with an -ly ending?" or "Should I be using the word ‘effect’ or ‘affect’?"

In these cases, you’ll be so glad to have access to the CMOS guides. After consulting one, you can confidently write: “We did affect the reaction by including 2 equiv. of the additive, as indicated by the color change, but we could not determine the effect of the additive on the reaction by NMR because the additive is paramagnetic.” Access blog posts and quizzes

If you’re a self-proclaimed grammar nerd like me or just curious about your grammar skills, you can access grammar quizzes. For example, the Chicago Style Workout 76 covers grammar standards from chapter 5. The workouts are quick, and you get the results and reference paragraphs immediately.

You’ll also find the blog CMOS Shop Talk, which reviews the if’s, when’s, why’s, and how’s of CMOS style conventions. Is CMOS Online worth the cost of subscription?

As a solopreneur with limited resources, I carefully consider every resource I purchase.

CMOS Online is one of the first resources I bought for my copy-editing business, and it’s been an incredible investment. It is my go-to resource for general usage and style conventions; I cannot edit without it. Have I convinced you that CMOS Online is worth the subscription price? Do you have more questions about CMOS? Tell me in the comments!

Have you ever almost used a semicolon, but abandoned the idea for fear of doing it wrong?

Or do you avoid semicolons because you worry they make your writing seem too stuffy? If so, you aren’t alone. Throughout modern history, semicolons have been one of the most misunderstood and polarizing punctuation marks in existence. For this reason, many writers shy away from using them altogether. There are strong opinions about the semicolon’s use. Some writers and editors believe it makes things too choppy. Others believe a comma and coordinating conjunction do the same job. Still others fear it makes their writing seem elitist. In this post, I’m coming to the defense of the semicolon. Get ready to learn more about what it is, how it is used, and why as an editor I use it often in my work. What is a semicolon?

According to Amy Einsohn’s and Marilyn Schwartz’s authoritative text The Copyeditor’s Handbook, the semicolon can act as a strong comma or a weak period.

How are semicolons used?

Most style manuals agree that the semicolon has three jobs:

1. To join two related independent clauses without using coordinating conjunctions 2. To precede a conjunctive adverb when linking independent clauses 3. To separate complicated items in lists where commas are already used. Semicolons can also be used to delineate items in references, but since reference formatting is not text writing, we won’t give into that here. However, if you’d like to learn more the University of Pittsburg Library system has a fantastic resource. Let’s break down each of those three uses with some examples. Using semicolons to directly join two related independent clauses

An independent clause is a clause that contains a subject and predicate that can stand alone, that is, it’s a complete sentence. Two related independent clauses have a logical connection to each other. With commas, a coordinating conjunction (“and”, “but”, “yet”) is needed to join two independent clauses. The short pause of the comma and the coordinating conjunction confirm that these ideas are related, but the comma may seem too hurried or trivializing. The long pause of a period may separate the ideas too much, thereby undermining some of the logical connection. The semicolon provides a middle ground for the pause—still evidencing the connection but allowing more space.

Using semicolons before conjunctive adverbs when linking independent clauses

Semicolons are also required when conjunctive adverbs (“however”, “therefore”, “indeed”, etc.) are used to combine two independent clauses. Adverbs qualify and describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, and even sentences. If one independent clause emphasizes or scrutinizes another independent clause, a conjunctive adverb preceded by a semicolon can be used to show this relationship between the clauses.

For example: “We aimed to create ideal conditions for the desired reaction; however, we still identified by-products in the batch.” Here, “however” emphasizes that we did our best to optimize and understand the reaction conditions. The substitution of “however” with “but” would emphasize the subsequent clause more. Separating items containing commas

If you list a series of items and one or more of the items has a comma, separating those items with commas may confuse your reader. Thus, a semicolon is warranted in this situation to separate the parts of the list.

“I’ve lived in Baltimore, Md; Tampa, Fl; and San Antonio, Tx.” Here a comma is conventionally used between the city and state so a semicolon should be used for clarity. “We optimized the reaction’s reagents; additives, bases to act as hydrogen ion scavengers; duration; and temperature.” I specify the type of additive and its function. But the meaning would be different if commas were used: “We optimized the reaction’s reagents, additives, bases to act as hydrogen ion scavengers, duration, and temperature.” This suggests that additives and bases were needed. Semicolons: Misunderstood and Undervalued

The jobs of a semicolon are straightforward. Still there are many people who find them frivolous or worse:

“If you have to use a semicolon, you didn’t write the sentence well enough,”—Personal communication. “All they do is show you’ve been to college,”—Kurt Vonnegut Jr. “They are more powerful more imposing more pretentious than a comma but they are a comma all the same. They really have within them deeply within them fundamentally within them the comma nature,” —Gertrude Stein. One argument against the semicolon is that a comma or period can do the same thing. Furthermore, because it gives a slightly longer pause than a comma, it may seem too strong or abrupt in some contexts. On the other hand, it is a shorter pause than a period and may seem too weak. In Defense of the Semicolon

,Personally, I think the semicolon has a place in a writer’s toolbox.

First, a semicolon can quickly fix comma splices, where two related—but independent—ideas have been joined with a comma. A semicolon can be swapped for that comma, making the sentence grammatically correct and retaining the intended pause and relationship. Second, and perhaps more importantly, semicolons help vary sentence length. As discussed in The Copyeditor’s Handbook, a writer can control the audience’s attention by varying sentence length. Too many short independent clauses ending in a period can give the writing a choppy feel. This choppiness leads to reader fatigue. In contrast, sentences that are too long can be confusing and unclear, leading to disinterest; therefore, intentional use of the semicolon helps retain the reader’s interest. Semicolon advocate Arthur Plotnik asserts in his book Spunk & Bite, “With a semicolon, there is a split-second of tease. . . . Semicolons inject expectation into sentences, and in literature expectancy is a good thing; it creates subliminal tension followed by release: the quiet ah’ of art.” Here is an example Plotkin’s idea in action. Take this sentence: “It was a dark and gloomy morning, and the houses almost disappeared as I walked past.” Although the sentence is technically correct, it lacks tension. But if we edit it to read as follows, much changes: “It was a dark and gloomy morning; the houses almost disappeared as I walked past.” The semicolon adds tension and begs the question, “where were you going?”. It's Time to Embrace the Semicolon

Whether you are a new writer or a seasoned one, it’s time to embrace the semicolon and use it to strengthen your writing.

Remember, semicolons can 1. provide longer pauses than commas and shorter pauses than periods 2. delineate relationships between related independent clauses 3. separate items in a complex list 4. add tension and interest to the text Did you learn something about semicolons? Please share my post on LinkedIn. I started my freelance copy editing and proofreading business when I was 39 years old. If I had been asked a decade earlier—just as I finished earning my doctorate in organic chemistry—if I ever imagined I’d be a business owner, the answer would have been “No.” As for many newly minted PhDs, I had a decision to make: what was next for me? Not only was I looking for a position at the beginning of the Great Recession but also was my husband of two years. It was difficult to find one chemistry position. But two? Our goal was to find two positions in the same city or region, not to live separately. However, after multiple offers for one of us or the other, but never both, I decided to become the trailing spouse. Although difficult for some, I was ready for a break from bench chemistry and willing to investigate an alternative, nontraditional career.

I lasted two months. My graduate advisor had told me that not working for a year or two was too long, and he was right. I was ready to get back into the lab, and as luck would have it, a postdoctoral position opened up at the same national lab as my husband’s postdoc position. There were many great things about my postdoc experience: I got my own funding, I learned a new branch of chemistry (and microbiology and mass spectrometry, etc.), and I worked with great people. Furthermore, I learned a lot about my passions and career goals. During my postdoc tenure, I had the opportunity to lead a class review session and teach an organic lab at a state university’s local campus. By the end of the three-year position, I had confidently decided a few things. Research is exciting and rewarding, but it’s not the career I wanted. The decision to leave a research career was easier because I also had a two-year-old daughter at home. Teaching wasn’t my passion either. Leaving the bench and the classroom was the right decision for me. For six years, I worked as a stay-at-home mom—yes, it is work! We had two more children, and keeping the kids fed, safe, and happy was a full-time job. This was a great time to pursue hobbies and find a community. Meanwhile, I was always thinking about what to do when all the kids were in school. I didn’t consider returning to research or teaching; those days were finished. I was considering nontraditional uses of my training that were flexible and preferably done at home. Language editing intrigued me because, during the last year of my postdoc, I was often frustrated by language errors I encountered in academic papers. The fields I was learning were complex, and poor writing made learning the science even harder. This soon became my passion. I was never taught how to write a scientific paper in graduate school. I followed the format of other papers from my group and purchased the ACS style guide; but, at the request of my advisor, I had to look for online writing tutorials to learn effective writing. Furthermore, I assumed most graduate students don’t receive writing training, although writing doesn’t come easily to everyone. Could I focus this discovered passion on helping others publish their research? Yes! There are many programs that provide training for language editing, copy editing, and proofreading, such as self-paced online certificate programs (Poytner) to actual enrollment at a university (UC San Diego) to obtain a degree or certificate. With my background in science and my experience in academic writing, I decided to try an entry-level, self-paced program that wasn’t too expensive or extensive. Within a year I had finished the course, joined the Editorial Freelance Association, gotten a freelancing/contractor job with an editing agency, and started my own freelance copyediting business--Scitech Proofreading. It quickly became apparent that there is a need for academic copy editors and proofreaders. Many scientists are multilingual, and writing in English can be especially difficult. Many agencies that provide editing services specialize in helping multilingual researchers write and edit so that they can publish their work. Working for these agencies provides experience and opportunities to perform many levels of editing. The hardest part has been directly finding clients for my freelancing business. Here, I’ve reached out to my network for leads, made new contacts with “cold” emails, and advertised my business—much like a job seeker. I’ve been blessed with finding a few repeat clients. I have been working as a part-time editor for three years. As a freelancer, I have control over my schedule and workload, which is exactly what I need as a mom of three kids. I’m encountering new research fields (e.g., materials science), new levels of editing and skills (e.g., macros), and how to be independently employed. It took a long time and some introspection to determine what my goals are and how to meet them. I may not always be a freelance editor, but currently this is the best fit for me. For those considering an alternative career in science, discovering your interests is key. Research programs where you can be trained in the required skills; reach out to your network for opportunities and leads; and freelance in the field if possible. Take the time to ascertain your strengths and weaknesses, determine your interests and passions, and be realistic about your material, social, and familial needs. Paraphrasing Paul Beverley, Advanced Professional Member CIEP and macro guru, macros are programs that, like apps, do something. Since I don’t know anything about coding, I will keep these comments brief. If you can imagine a macro to do a particular task, you (or someone who does know coding) can probably write one to do it. I started using macros when a LinkedIn connection mentioned Paul Beverley and macros helping with the editing process. Once I started working with macros, I quickly realized how macros can improve my accuracy and efficiency. So, here is how I use macros in my copy editing and proofreading.

I have three phases of editing and macros come in handy in each of them. In the first phase, I use macros to set the language of the entire document, highlight potential article usage errors, pull out potential spelling errors, and so on. Usually a hard and fast rule applies to these types of errors and I can quickly mark them for later or make decisions on them right away. For example, the journal article must be written in UK English; or certain field-specific words aren’t found in my dictionary, so I look them up to confirm spelling and then use a macro to highlight the truly incorrect words. Macros allow me to do this quickly and efficiently; they give me a sense of how much editing will be needed in the document and what I errors I need to be on the lookout for. In my second phase of editing, I consistently use a different set of macros. My current favorites include “InstantJumpUp/Down”, “PunctuationToTimesSign”, “WhatChar”, and “CommentJumpInOut”. If I’m not if a special character is the correct one, I use the “WhatChar” macro to find out. Do I need to go to the next instance of a phrase? I use “InstantJumpDown”. These are assigned shortcut keys so that I can almost exclusively use the keyboard instead of the mouse—thereby avoiding repetitive strain injury (more on that in another blog)—allowing me to quickly edit throughout the manuscript. My final phase is clean. I run the usual spellcheck and find and replace tools. I use a macro to tabulate my comments so that I can double check them for consistency and errors. My favorite macros at this stage are “HighlightFindDown” and “UnHighlightAndColour”. Instead of paging through the text, I can quickly go to a highlighted section and then remove that same color within the rest of the paper. There you go! These are the Paul Beverley macros that I find helpful and use for almost every editing and writing project. Not only can you get these macros free from Paul Beverley, but he has a YouTube channel on how to use macros. Now go out there and learn how to use these powerful tools! Why do you need a proofreader? Here are four reasons: typos, grammar, diction, and syntax. This blog is about those innocent mistakes—typos. In any field, typos, short for typographical errors, can cost time and money, but in research and science, typos can cost you credibility as well.

It is difficult to plan, write, and publish scientific papers. Not only do you need to organize your research logically, but you also need to submit the manuscript to an appropriate journal and satisfy peer review critiques. Typos are distractions to your audience and can cause delay in publication. Even worse, typos, no matter how innocent, may cost you credibility with your audience. Why, you may ask? Surely everyone makes these mistakes, right? Yes. But the meticulous author will go through the manuscript with a fine-tooth comb to try to catch these errors. A researcher may be considered lazy if the manuscript is riddled with typos. Furthermore, this perception of laziness in the writing process may shift to a conception that the scientist was also lazy during research. At best, typos cause delay or distraction, but at worst they can be embarrassing or hurt your reputation. Here's an example from my own life that shows how a simple typo may have cost me credibility as a capable researcher. Although this example isn’t from a paper I wrote, it shows how a small typo can cause big embarrassment. I was presenting my research at a job interview. Most of the slides were made months before and had been presented at group meetings more than once. I was in the groove; describing the why and how of my doctorate research. Everything was going well, until an audience member raised his hand and said, “Did you know you have a typo on that slide? Your group mates should have caught that.” What typo? Where? I stumbled; it took me a few moments to even find the typo. I had written a chemical formula wrong: LiAl4H instead of LiAlH4. One simple mistake and my whole presentation was thrown off. Did this error cost me a job offer? Probably not; I made a few other mistakes that day. But it was embarrassing, and it did not convey the message that I was prepared for my interview. Proofreading is an extremely important step for scientific and technical writing. We all make mistakes and a proofreader’s job is to find those remaining typos. If you don’t have the budget for a proofreader, make sure every author has read through the text thoroughly and ask a peer not involved in writing to take a look. Even if you think you don’t have time, don’t skip this step. Leaving easily fixed mistakes in your manuscript may cost you more than you expect. |

AuthorSusan is a scientist turned writing service specialist. Her interests include the clear communication of scientific research and complex subjects. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed